Introduction

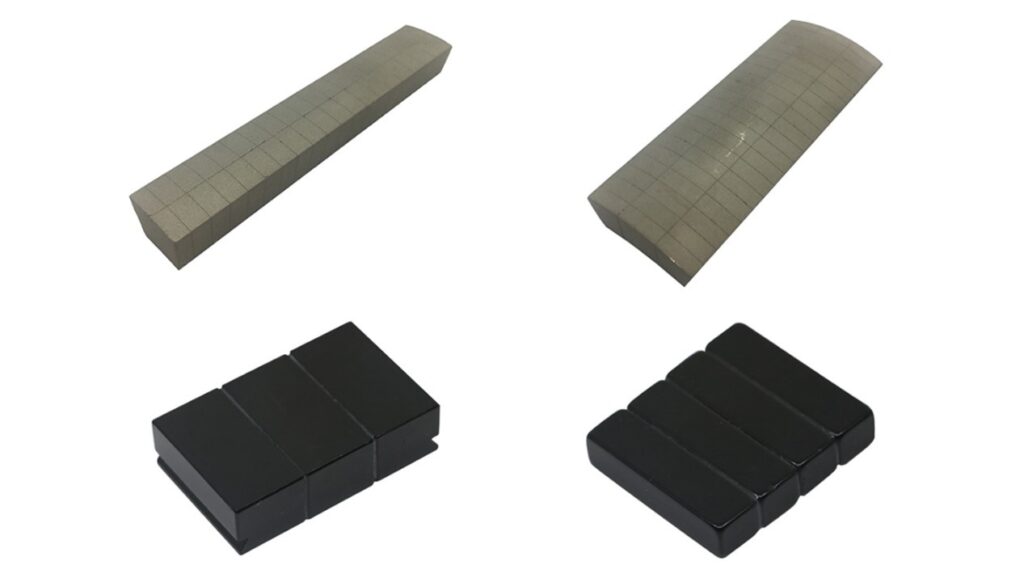

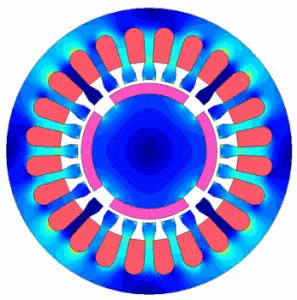

In the engineering and design of rotating machinery, such as electric motors, one critical challenge that must be addressed is the phenomenon of eddy current losses, particularly in materials used for magnetic components. Samarium-cobalt (SmCo) and neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, being metallic and possessing excellent conductivity due to their low resistivity, inherently face this issue. Eddy current losses not only lead to inefficient operation by generating unnecessary heat within the rotating machinery, including the magnets themselves, but also can degrade the magnets over time. EPI Magnets aims to shed light on the nature of eddy current losses in magnets and explores strategies to minimize these losses in the production of magnetic materials.

Skin Effect

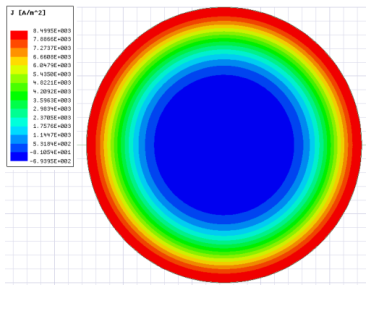

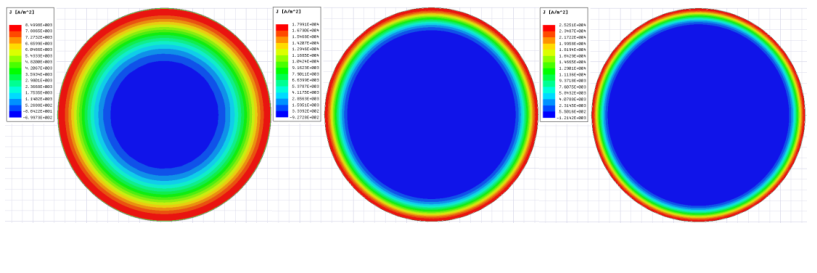

Understanding and mitigating eddy current losses begin with comprehending their origin, tied closely to the skin effect. The skin effect occurs when alternating current flows through a conductor, leading to a non-uniform distribution of current density across the conductor’s cross-section. As the frequency of the current increases, the current tends to concentrate more on the surface of the conductor, reducing the effective cross-sectional area through which the current flows. This phenomenon is primarily caused by eddy currents—vortex-like currents induced within the conductor by the changing magnetic field associated with alternating current.

Delving deeper into the mechanisms behind the skin effect reveals its intimate connection with eddy currents. Eddy currents, or swirls of electric current, are induced within a conductor due to the changing magnetic fields that accompany alternating electric currents, a principle outlined by the law of electromagnetic induction. As alternating current flows through a conductor, it generates a changing magnetic field both within and around the conductor. This changing magnetic field, in turn, induces vortex-like currents inside the conductor, known as eddy currents.

The impact of these eddy currents becomes more pronounced closer to the center of the conductor, where the induced electromotive force (EMF) by the changing magnetic field is stronger. This results in more robust eddy currents that provide greater resistance to the original current flow, leading to a decrease in current density near the center of the conductor and an increase near its surface.

Furthermore, as the frequency of the alternating current increases, the induced EMF—and consequently, the strength of the eddy currents—also increases. This amplifies the skin effect, causing the current to be confined even more to a thin layer at the conductor’s surface. At very high frequencies, the current effectively flows only through this thin surface layer, effectively reducing the conductor’s cross-sectional area available for current flow and significantly diminishing the material’s effective utilization rate.

Understanding this intricate relationship between eddy currents and the skin effect is crucial for devising strategies to mitigate eddy current losses. By acknowledging how these currents influence magnetic and electrical properties, especially in applications involving rare earth permanent magnets, engineers can better design materials and systems that minimize these losses, thereby enhancing efficiency and performance.

Eddy Current Losses

Given the low electrical resistance of SmCo and NdFeB permanent magnets, they are particularly susceptible to significant eddy currents when exposed to alternating magnetic fields. These eddy currents generate heat through Joule heating, which can lead to thermal demagnetization if the temperature becomes excessively high.

The extent of eddy current losses is influenced by factors such as the change in the magnetic field, the movement of the magnet, its shape, magnetic permeability, and electrical resistivity. In applications like electric vehicles and elevators where speed control is critical, and power is often supplied by inverters, the higher harmonics of the carrier frequency can exacerbate eddy current losses, leading to thermal demagnetization.

Reducing Eddy Current Losses